This is the most comprehensive guide on the internet for finding and identifying cheap anvils. Finding an anvil when you first begin blacksmithing can be difficult. Make the process easier by reading this anvil guide where we review the best anvils, and explain everything you could ever want to know about anvils…

I remember the difficulty of choosing my first anvil, I had just graduated from university when I began my blacksmithing journey. Reeling from student loans, I found myself on a bit of a budget. I was desperate to begin my journey as a blacksmith, but I needed a cheap anvil. The cheapest option at that time was to find an anvil that was being sold locally. I found the process of finding an anvil to be incredibly tedious. I just wanted to bend metal! I wanted to build something beautiful; I wanted to build something that was uniquely my own. I wanted something no one else in the world could possibly ever own…and these desires were being held up by my inability to find the most basic of all metal working instruments: an anvil.

Luckily things have changed quite a bit since I first began blacksmithing. It is now incredibly easy to find anvils online. In fact, there is a large selection of anvils available. If you just want to dip your toe into the world of metalworking (wear boots), there are a number of quality cheap anvils for sale on the market.

Three Cheap Anvils

If you are simply looking for the lowest price tag possible, then this is it! This little beauty is 9 pounds of solid cast iron. Don’t let the weight fool you, this tiny anvil could easily fit into your calloused metal-working hands. This cheap anvil does contain a hardie hole, but it lacks a pritchel hole. It has a smooth face that extends out into an elegant horn. I should note that this anvil does not have the traditional step between the face and the horn. This is an excellent anvil for softer metals (such as brass), and fine-jewelry making. If you are looking for an anvil that can handle knife making, I recommend a larger anvil with a steel face. All-in-all, this is a wonderful anvil that is great for leather-working and fine jewelry making.

If you are looking for a more traditional sized anvil, this is a reasonably priced mid-tier anvil that weighs in at 55lb. This is a cast iron model that comes with a pleasant blue coat. Like the smaller model analyzed earlier, this anvil contains a hardie hole but lacks a pritchel hole. Unlike the smaller model, this mid-ranged anvil does contain the traditional step between the face and the horn of the anvil. Although I still recommend a steel anvil for serious blacksmithing work, this is a good starter anvil for hobbyists who are taking their first steps as a craftsman. With this anvil as a base, an aspiring smith will be able to lovingly hand-craft all the tools needed for future projects. There is nothing more satisfying than holding a one of a kind tool, created by a devoted craftsman (you)!

Next up is an anvil that is simply beautiful. Weighing in at 68 pounds this steel farrier anvil has ALL the bell’s and whistles. Unlike the previous models, this bad boy contains a pritchel hole in addition to it’s 1” hardie hole. This model also contains a turning “fork” or “cam” on the heel of the anvil which is incredibly handy. This anvil is American made by a company called Big Face in North Carolina. There is a handsome horseshoe logo on the side of the anvil. This thing has the roundest horn I have ever seen. This is no cheap anvil, this thing is dang impressive. If you are serious about your future as a smith, consider buying one at

This final anvil is for people who are looking for a tough anvil that can handle absolutely anything they can hit it with. This anvil is drop-forged from high-grade steel and is made by the most precise engineers in the world. This product of German manufacturing weighs in at 285 pounds and can handle some of the toughest smith work out there. This anvil has an incredible bounce, and is an absolute pleasure to work with. I recommend this anvil to serious smith’s only, as it is quite an investment.

It’s important to view your anvil purchase as an investment. A good anvil, which is well maintained, will serve you well for your entire life. Having a trusty anvil which you can always count on will allow you to focus your creative energies on building the things that matter most to you. I know from experience, you DO NOT want to be worrying about your tools when your forge fires are roaring and your creative juices are flowing. Nothing breaks you out of a state of flow faster than fiddling with an anvil which is not quite right for the job. You are a hard working person, do yourself a favour and buy a good anvil. You will not regret it.

Most importantly, don’t fall victim to paralysis-by-analysis. You are budding craftsman waiting to bloom, the quicker you buy your anvil, the quicker you can begin crafting elegant metallic beauty the likes of which the world has never seen before. Dive head first into your new craft, and don’t let anyone stand in your way!

While I recommend aspiring blacksmiths to make all their own tools, it does help to have a hammer in addition to your anvil. A good hammer will allow you to make your uniquely-you tools with the precision you need. Luckily hammers are much cheaper than anvils, and I recommend you simply buy one. If you would like an in-depth guide on the different types of blacksmith hammers (there are many), check out my guide on blacksmith hammers.

Still undecided? Info On The Parts Of An Anvil

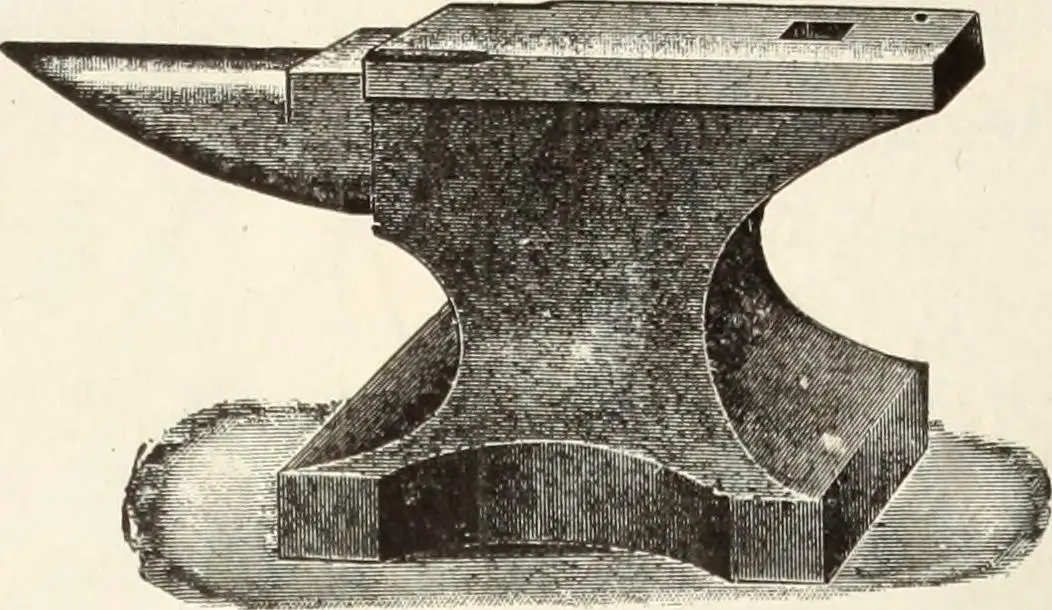

Anvils are simple enough as far as far as tools go. At the bottom of a typical London style anvil is the base. The base is composed of four feet. Above the base and feed sits the waist. The waist features a reduction in width that creates a semi-hourglass type shape. This allows for a larger surface area in the base and the all important striking area. This helps maintain a good ratio of weight to striking surface. Some models of anvils feature holes in the feet that allow the smith to clamp the anvil to a table or a stand. Above the anvil’s waist lies it’s body. This is basically the featureless mass of metal that lies below all the good stuff.

Above the body and lying towards the back of the striking surface is the anvil’s heel. The typical London style anvil has a square heel. Some models have forked heels, so make sure you know what type you are looking for and buy the appropriate anvil. On most london pattern anvils two holes lie just beyond the anvil’s heel. There is a Hardie Hole which is a square hole, and a pritchel hole which is a smaller round hole. These holes are useful for a number of blacksmithing actions such as punching a hole into a piece of metal or holding tools that have a round shank. The hardie hole is a larger hole and can be used for punching,bending, and cutting operations.

In front of these two holes and in the middle of the striking surface is a flat area known as the face of the anvil. This is a hard central plane, and it’s where most of the striking actions will take place. This allows the smith to create objects that are flat which is important for both aesthetics and utility. Going further down the top surface of the Anvil lies an area that goes by a number of different names. This little ledge which lies between the face and the horn may be called a table,shelf, or a step depending on the source. Not all anvils have this feature, but it is common for the London pattern anvil. Finally, at the front of the anvil lies the eye-catching anvil horn. This is a rounded point that looks….like a horn. The horn of an anvil is incredibly useful for bending metal into circular shapes. The horn tapers as it goes out to the point, allowing the smith to create bends of varying degrees.

If you are interested in other designs, check out this post on Anvil Types

Alternative Types Of Anvil’s

The main goal of an anvil is to be hard and immovable. A lot of the other features – such as holding tools, or providing a shape to act as a swage – are optional. As such, you can really get creative if you need a quick and dirty anvil alternative. For example: I have seen a number of people screw a piece of mild steel into a stump. This is not a perfect anvil; it will be soft compared to high grade anvils, which means it may dent. It will also fail the “bounce test”. All that aside, it will be immovable and hard enough.

another alternative – more of a compliment really – to the traditional anvil is called a swage block. Swage blocks are heavy hunks of metal that contain cavities in the surface that are used for special blacksmithing functions such as bending, cutting, and forming. The cavities will often hold unique shapes, as many artisanal smiths will have their swage block custom made for their particular product lines. These “anvils” can greatly increase productivity if the smith finds himself making certain products over and over again.

Because so many swage blocks are custom made, you can see some pretty interesting ones. One that stands out in my mind was one that was a anvil/swage block hybrid. It’s always interesting to me to see so much utility formed into a solid hunk of steel!

Another anvil variant is known as the hornless anvil. It’s pretty self explanatory to be honest. It’s an anvil without a horn, this may be useful in situations where there is limited space and the owner of the anvil doesn’t need to use the horn often.

Finally, you have the classic anvil-shaped-object, also known as an ASO. These objects do not look like traditional anvils, but they get the job done. Really all you need for an anvil is something that is hard,flat, and stable. A common ASO that you see on youtube is the railroad track anvil. I would recommend being careful with that however, as there are odd legalities involved with railroad property. Because of this, it can actually be difficult to find the necessary raw materials to make a railroad track anvil!

History of the Anvil

The anvil, as we typically think of it today is built via the “London Pattern.” This a type of anvil that was created in the 1800’s.There were a large number of anvils that were in use before this. Humans have been smithing metal since the dawn of civilization. In fact, some historians refer to various ages in the development of human civilization based on the metal working capabilities of the civilizations in question ie: bronze age.

If you are feeling self-conscious about your desire for a cheap anvil, you shouldn’t worry yourself. You are joining a craft that has a history that goes back thousands of years. Ancient smiths most likely did not have a standard anvil as we think of it today. They probably used any flat surface they could find that was sufficiently sturdy and up to the task. Civilizations in which metalworking was a vital and central economic activity tended to use better anvils as opposed to makeshift anvils in order to increase efficiency and ease of use. Luckily for you, even the cheapest anvils for sale today vastly outrank these ancient anvils.

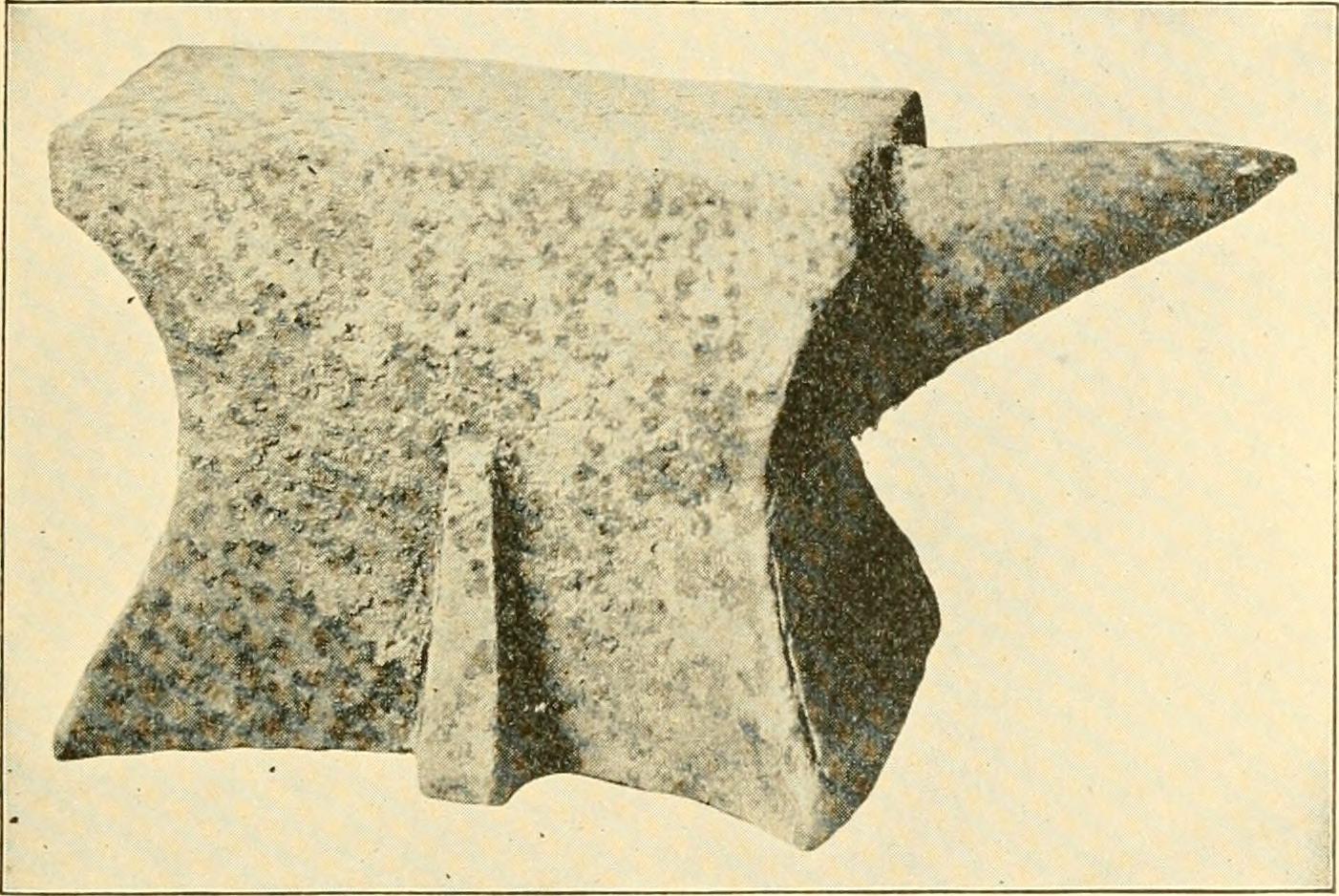

What did these ancient anvil’s look like? It various wildly by geography and the civilization in question. Some ancient anvils appear to be made out of meteorite. Others were created out of stone slabs or even bronze slabs. Eventually smiths moved on to the tougher and more reliable iron or steel anvils. It’s important that you don’t stress yourself too much about buying the perfect anvil; Even if you are just looking for a cheap anvil, the important thing is to get started and learn through trial and error. Books and informative internet articles are an important part of your education, but at the end of the day you must simply make things!

If you want a real, comprehensive look at the history of the anvil, I highly recommend the books Anvils In America and Anvils Through The Ages. While I try to provide the best information possible in my articles, it’s just not possible to convey as much information as can be found in books. If you are interested in other great blacksmithing books, check out my article that compiles some of the most useful blacksmith books out there.

What to look for in an Anvil

A major factor to consider is an anvils “bounce”. Many people want an anvil that sends the hammer flying back up into the sky after you strike a piece of metal. The idea is that this reduces the amount of effort a smith must use as he no longer has to exert himself quite so hard to bring the hammer back up.

However a number of people have also come out and stated that this is all hogwash, as all the energy from the blow will get transferred to the stock being worked on.

I will remain agnostic on this particular issue, but it’s a factor many consider to be important, so I thought it was worth mentioning.

Anyhow, the primary factor of anvil bounce is the anvils composition, which leads too…

Anvil Composition

A major factor one must consider when buying an anvil is the metallic composition of an anvil. Cast iron anvils are generally cheaper, but they provide less of a bounce back and may crack with use over time – cast iron is more brittle than other types of metal we will discuss. Higher quality anvils are made from cast or forged steel, with forged steel generally being the strongest. Softer anvils such as wrought iron anvils (not common anymore), will get beat up with use.

Anvil’s in Art

Cheap anvils and expensive anvils alike both get used in various art forms. They are often used as percussion instruments, as striking an anvil creates a very unique sound that can create some incredible atmospheric effects. For example, anvils are used in Richard Wagner’s Das Rheingold which is the first of the four Der Ring des Nibelungen operas. On a more contemporary note, anvils are featured in Judas Priest’s 1990 song “Between the Hammer & the Anvil.” How Metal is that!

Anvil Firing

This is the amusing but dangerous practice of launching an anvil hundreds of feet into the air via a gunpowder explosion. This is done typically but placing one cheap anvil upside down, and filling a hollowed out base with gunpowder. A second anvil is placed squarely on top of it, and a fuse is set between them. Depending on the particular anvils and gunpowder used, this practice can launch the top anvil hundreds of feet into the air. This used to be done as a celebratory event in some cultures. Today this is seen as dangerous, and it’s recommended that amateurs do not attempt this, leave it to the experts.

What is a Farrier

A farrier is a specialist who focuses on the care of horse hooves and horse shoes. Farriers combine blacksmithing knowledge with veterinarian knowledge to ensure that the horses under their care have healthy hooves. From a historical standpoint, Blacksmiths were farriers and vice versa, however today they tend to be distinct specialties despite the fact that farriers use certain blacksmithing techniques. In fact, you can see this ancient amalgamation of the two specialties in the word itself. Farrier is based on the middle french word ferrier (blacksmith), and from the Latin word ferrum (which means iron).The influence of ferrum is widely felt and can be seen any time people talk about ferrous materials (iron materials). Some anvil designs are specifically tailored to the work of the farrier. These specialized anvils are sometimes more expensive, and can’t be considered cheap anvils.

The Journey of Iron

The life of elemental iron actually begins in the stars. While it’s actually an incredibly complicated and very interesting subject in itself, I will try to condense it down to the simplest points. At some point, very large stars begin creating iron in their cores, this iron disrupts the stars “battling” forces of gravity and fusion. The end of this war of opposing forces eventually leads to the destruction of the star itself. At some point in the process, the created iron is expelled from the star’s core into the universe. Think of that next time you cook with iron cookware!

Despite its incredible interstellar origin, iron on earth is often further manipulated by man, so that it is more useful for certain purposes. This is relevant, as it’s this process of manipulation that leads to the different types of anvils and metals we use today.

Iron is readily reactive to oxygen, this creates iron oxide and means that iron is hard to find in readily usable form on the surface of planet earth. In order to remove oxygen, early smiths would burn iron ores in charcoal furnaces called bloomeries. The burning of charcoal in these bloomeries creates carbon monoxide, which in turn reacts to the iron oxide in the iron ore. This reaction results in carbon dioxide and Iron. The heavier iron falls to the bottom of the bloomery, and the lighter waste materials (called slag) rises to the top. When the iron is removed, it is still mixed with impurities, and the iron needs to be heated up and beaten with a hammer. This removes the impurities and eventually leads to wrought iron.

Wrought iron has an incredibly low carbon content. In fact, wrought irons carbon content is less than 0.08%. This makes it less hard than other forms of iron, but it is more ductile. The problem with creating wrought iron from bloomeries is that it’s a very uneconomical process, as bloomies only produce a small amount of wrought iron. This was particularly true before the use of water wheels to power furnace bellows.

The Industrialization of Steel for Anvils

Blast furnaces were eventually invented to allow the smelters to obtain more iron. The blast furnace works similarly to the bloomery in that it burns away the carbon oxide, but it operates at a much higher temperature. This higher temperature brings more carbon into the iron, creating cast iron or pig iron.

Cast iron has a carbon content of over 2%, which is significantly higher than wrought iron. This makes it much harder than wrought iron, but it is also significantly more brittle. This brittleness is a severe drawback for certain applications. For example, cast iron cannons had a bad habit of blowing up, and cast iron bridges would often fall due to cast irons lower ductility.

To reduce the carbon content of cast iron, industrialist began utilizing the Bessemer process. This process allowed industrialists to produce large quantities of steel cheaply. This was important for economic growth as steel has a carbon content between pig iron and wrought iron. This gives steel a good balance between hardness and ductility that is vitally important for heavy use projects such as infrastructure projects. The Bessemer process works by by removing impurities from iron by oxidation. This oxidation also helps raise the temperature of the iron mass.

However there were problems with the Bessemer process. While it greatly increased the quantity of steel produced, there were a lot of quality problems. The Bessemer process happened relatively quickly, which made it difficult to control the process and measure the changes in the raw material. Steel made through the Bessemer process tended to have too much nitrogen, this caused the steel to be brittle. Bessemer steel was too brittle for vital structures.

Just as the Bessemer process was getting into full swing, another steel making process was developed. This process utilized an open hearth furnace. Open hearth furnaces allowed large batches of steel to be made, but the overall process was significantly slower than the Bessemer process. This decreased speed allowed manufacturers to better control the quality of the steel and avoid the problems of high nitrogen levels. This process complimented the Bessemer process, as it allowed higher quality but more expensive steel to be made.

Over the last 50 years, electronic instruments were developed that made the analysis of steel being produced significantly easier. This made the old methods for steel production unnecessarily slow and inefficient. In today’s world, much of the steel used in anvils and other products are created via a process known as basic oxygen steel making. Much like the previous processes discussed, The basic oxygen steel making process takes carbon rich pig iron and turns it into steel. Unlike the Bessemer process, the BOS blows oxygen (as opposed to air) at a high pressure into the cast iron. The manufactures also pay close attention to the ph level of the steel making environment, according to Wikipedia, they try to keep it above 3 through utilizing basic refractories and adding basic materials if needed. I have simplified the process a bit, but if you are interested I highly recommend that you check out the Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_oxygen_steelmaking.

While that might seem like information overload to a beginner looking for a new anvil, I personal am always curious as to how the underlying materials of an object are made. Thinking about the steel making process may also help develop your intuition while you are working on your own projects!

What This Means For Anvil Selection

All this information is important when selecting an anvil. Cast iron makes for good cheap anvils, however, as we have discussed, cast iron is more brittle and more prone to major collapses. Steel anvils will be more expensive than cast iron anvils, as they have to go through more industrial processing, but they will be more ductile (durable). While it’s tempting to grab the cheapest anvil possible, I highly recommend spending more to obtain a steel anvil.

History Of The Blacksmith and The Anvil

Gold, silver, and copper all occur in nature in their natural states. Unliked iron, they do not have to deal with the oxidation process. This made it much easier for early humans to work these metals and they developed them first. These metals are malleable, and lead to the first developments in the striking of metal. During the bronze age, humans discovered how to create bronze, which is an alloy of copper and tin. Bronze is better than copper, as it is harder and less likely to corrode. During the peak of the bronze age, most copper was mined from the island of cyprus, and most tin came from the cornwall region of Great Britain. This made bronze inaccessible and was another factor for the future success of iron. During this time anvils could be made of bronze or could even be composed of a large slab of rock.

During the bronze age, some civilizations tinkered with meteoric iron, this type of iron had a high nickel content that went as high as 40%. This type of iron was exceptionally rare, and was not a common enough element to spur major technological innovation and growth. An ancient civilization called the Hittites of Anatolia appeared to be the first civilization to really start using iron in a large scale way. They first began using iron around 1500 B.C. The knowledge seemed to spread outwards towards all corners of the world.

When iron was first adopted, it was often inferior to the old copper swords as it was softer. Iron was much cheaper to obtain however, and slowly began to fill the lives of ancient denizens in every aspect from farming to warfare. Iron plows are stronger and heavier than their bronze counterparts. This made farmers more productive, and in turn lead to an increase in specialization and the further development of civilization. I believe that during this period, it’s likely that ancient blacksmiths began using wrought iron to construct their anvils.

If you are looking for a smaller anvil for jewelry making and other precision crafts, check out my article on riveting anvils.